It was the first day of my first Erlang-based system in production. I’ve invested some sensible amount of time to test and stabilize it. I’s were dotted, t’s were crossed and I felt confident that it would work reasonably well. The system broke in production within the first few hours of its life.

The breakage was caused by the excessive usage of the ++ operator. I was iteratively building a large list by appending new chunks to its end, which is extremely inefficient in Erlang. Why did I do it then? Because I didn’t know better :-) I incorrectly assumed, based on my experience with other languages, that in the expression list_a ++ list_b only list_b is being iterated (which would have been fine).

This incident took me down the path of prepends, right folds, and reverses, and taught me that dealing with sequences in Erlang is very different compared to what I’ve seen so far. After a couple of other issues I realized that choosing a data structure to represent a sequence is highly context-sensitive in Erlang, much more than in many other languages I’ve seen until that point. For better or worse (probably worse, more on that later), in BEAM languages we’re lacking a solid all-rounder, a structure which might be a sensible default choice for most cases.

For the purpose of this article, the term sequence means an ordered collection of things. For example, a list [:foo, :bar, :baz] is a sequence because the structure preserves the information that foo comes before bar, which in turn comes before baz. On the other hand, a MapSet containing those same elements will not preserve that order (in fact, the internal order in this particular case will be bar, baz, foo).

Sequences can be used in a bunch of different ways. For example sometimes we might need to walk it from start to end, in the given order. Other times we might want to work on elements based on their position (e.g. get the 3rd element, or replace the fifth one). This is known as a random-access operation, and it’s going to play an important role in choosing an optimal data structure to represent our sequence.

In this post I’ll go over a couple (but not all) of data structures that can be used to model a sequence. In particular we’ll take a look at lists, arrays, maps, and tuples, discuss their trade-offs, and compare their performances through a set of simple and fairly naive benchmarks. The results we’ll obtain won’t exactly be scientific-paper grade, but we should get some basic intuition about which structure works best in different scenarios :-)

Lists

A frequent choice for representing a sequence, lists deceptively resemble arrays from many other languages. However, lists are nothing like arrays, and if you treat them as such you might end up in problems. Think of lists as singly linked lists, and the trade-offs should become clearer.

Prepending an element to the list is very fast and creates zero garbage, which is the reason why lists are the fastest option for iteratively building a sequence the size of which is not known upfront. The same holds for reading and popping the list head (the first element). Getting the next element is a matter of a single pointer dereference, so walking the entire list (or some prefix of it) is also very efficient. Finally, it’s worth noting that lists receive some syntactic love from the language, most notably with first class support for pattern matching, which often leads to a nice expressive code.

These is pretty much the complete list of things lists are good at. They basically suck at everything else :-) Random-access read (fetching the n-th element) boils down to a sequential scan. Random-access writes will additionally have to rebuild the entire prefix up to and including the element which is changed. The length function (and consequently also Enum.count) will walk the entire list to count the number of elements.

Consequently, lists are not a general purpose sequence data structure, and treating them as such may get you into trouble. To be clear, doing an occasional iterative operation, e.g. Enum.at, length, or even List.replace_at doesn’t necessarily have to be a problem, especially if the list is small. On the other hand, performing frequent random-access operations against a larger list inside a tight loop is probably best avoided.

Arrays

Somewhat less well-known, the :array module from the Erlang’s stdlib offers fast random-access operations, and can also be used to handle sparse arrays. The memory overhead of an array is also significantly smaller compared to list. Arrays are the only data structure presented here which is completely implemented in Erlang code. Internally, arrays are represented as a tree of small tuples. As we’ll see from the benchmarks, small tuples have excellent random-access read & write performance. Relying on them allows :array to offer pretty good all-round performance. I wonder if the results would be even better if :array was implemented natively.

Maps

A sequence can be represented with a map where keys are element indices. Here’s a basic sketch:

# initialization

seq = %{}

# append

seq = Map.put(seq, map_size(seq), value)

# random-access read

Map.fetch!(seq, index)

# random-access write

Map.put(seq, index, new_value)

# sequential walk

Enum.each(

0..(map_size(seq) - 1),

fn index -> do_something_with(Map.fetch!(seq, index)) end

)

At first glance using a general-purpose k-v might seem hacky, but in my experience it can work quite well for moderately sized sequences. Map-powered sequences are my frequent choice if random-access operations, especially reads, are called for, and I’ve had good experiences with them, not only for basic one-dimensional sequences, but also for matrices (e.g. by using {x, y} for keys) and sparse arrays.

On the flip side, maps will suck where lists excel. Building a sequence incrementally is much slower. The same holds for sequential traversal through the entire sequence. However, maps will suck at these things much less than lists suck at random access. In addition, building a sequence and walking it are frequently one-off operations, while random access is more often performed inside a loop. Therefore, maps may provide a better overall performance, but only if you need random access. Otherwise, it’s probably better to stick with lists.

It’s also worth mentioning that maps will introduce a significantly higher memory overhead (about 3x more than arrays)

I personally consider maps to be an alternative to arrays. More often than not I start with maps for a couple of reasons:

- Maps are slightly faster at reading from “medium sized” sequences (around 10k elements).

- They can elegantly handle a wider range of scenarios (e.g. matrices, negative indices, prepends).

-

The interface is more “Elixiry”, while

:arrayfunctions (like many other Erlang functions) take the subject (array) as the last argument.

Tuples

Tuples are typically used to throw a couple of values together, e.g. in Erlang records, keywords/proplists, or ok/error tuples. However, they can also be an interesting choice to handle random-access reads from a constant sequence, i.e. a sequence that, once built, doesn’t change. Here’s how we can implement a tuple-based sequence:

# We're building the complete list (which is fast), and then convert it into

# a tuple with a single fast call.

seq = build_list() |> List.to_tuple()

# random-access read

elem(seq, index)

# iteration

Enum.each(

0..(tuple_size(seq) - 1),

fn index -> do_something_with(elem(seq, index)) end

)As we’ll see from the benchmark, random-access read from a tuple is a very fast operation. Moreover, compared to other structures, the memory overhead of tuples is going to be much smaller (about 20% less than arrays, 2x less than lists, and 3.7x less than maps). On the flip side, modifying a single element copies the entire tuple, and will therefore be pretty slow, except for very small tuples. Finally, It’s also worth mentioning that maximum tuple size is 16,777,215 elements, so tuples won’t work for unbounded collections.

Benchmarking

We’ll compare the performance of these different data structures in the following scenarios: iterative building, sequential walk, random-access reads and writes. The benching code can be found here. The results have been obtained on a i7-8565U CPU.

Before we start analyzing the results, I want to make a couple of important points. First, these benches are not very detailed, so don’t consider them as some ultimate proof of anything.

Moreover, bear in mind that data structure is only a part of the story. Often the bulk of the processing will take place outside of the generic data structure code. For example while iterating a sequence the processing time of each element will likely dominate over the iteration time, so a switch to a more efficient data structure might not lead to any relevant improvements in the grand scheme of things.

Sometimes a problem-specific optimization can lead to much more drastic improvements. For example, suppose the program is doing 1M random-access operations. If, taking the specific problem into account, we can change the algorithm to reduce that to e.g. 20 operations, we could get radical improvements, to the point where the choice of the data structure isn’t relevant anymore.

Therefore, treat these results carefully, and always measure in the context of the actual problem. Just because A is 1000x faster than B, doesn’t mean that replacing B with A will give you any significant performance gains.

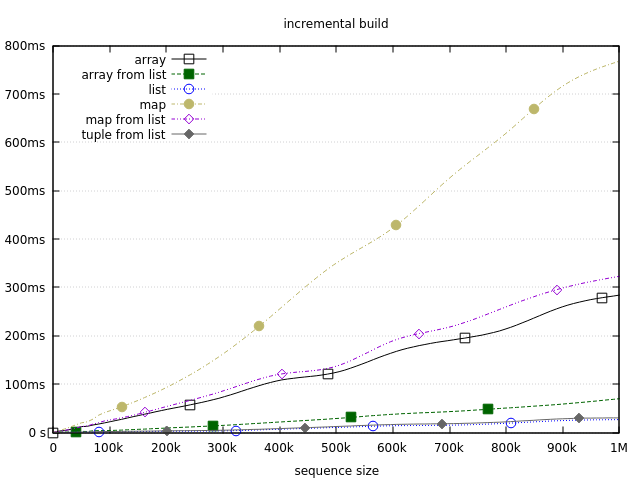

Building a sequence

Let’s first compare the performance of building a sequence incrementally. Here are the results:

The measurements are performed on various sizes: 1, 2, 3, …, 10, 20, 30, …, 100, …, 1M. For the sake of better identification of each measurement, a few points on each line are highlighted (circles, squares, …).

The results demonstrate that lists are the fastest option for dynamically building a sequence. The 2nd- and the 3rd- best option also owe their results to lists. In both of these cases we first build a list, and then convert it to a target structure with List.to_tuple and :array.from_list respectively. List.to_tuple is particularly fast since it’s implemented natively. It takes a few milliseconds to transform a list of million elements into a tuple on my machine.

Gradually growing arrays or maps is going to be slower, with maps being particularly bad, taking almost a second to build a sequence of 1M elements. However, I’m usually not too worried about it. In the lower-to-medium range (up to about 10k elements) growing a map will be reasonably fast. When it comes to larger sequences, I personally try to avoid them if possible. If I need to deal with hundreds of thousand or millions of “things”, I usually look for other options, such as streaming or chunking, to keep the memory usage stable. Another alternative are ETS tables, which might work faster in such cases since they are non-persistent and reside off-heap (I discussed this a while ago in this post).

Memory usage

It’s also worth checking the memory usage of each structure. I used :erts_debug.size on a sequence of 100k :ok elements, and got the following results:

- tuple: 100k words

- array: 123k words

- list: 200k words

- map: 377k words

Unsurprisingly, tuples have the smallest footprint, with arrays adding some 20% extra overhead. A list will require one additional word per each item, and finally a map will take up quite a lot of extra space.

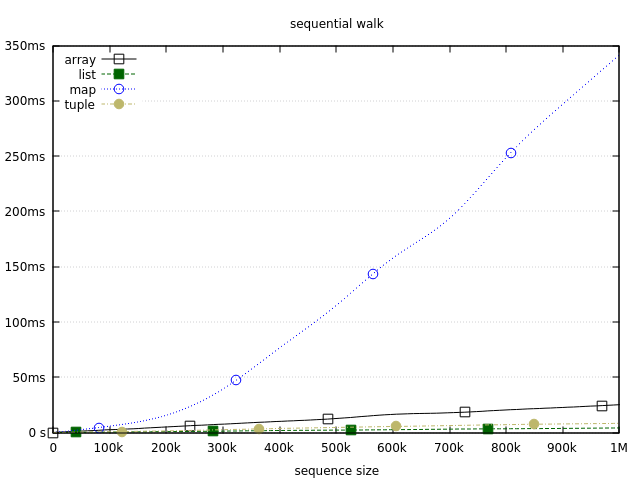

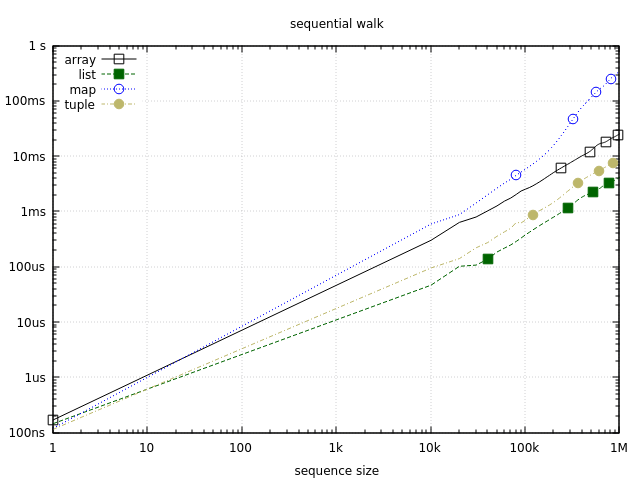

Walking a collection

Next up let’s see how long it takes to sequentially walk through the entire sequence. Note that tuples and maps don’t support ordered traversal, so we have to resort to random-access reads (get the 1st element, then the 2nd, …).

This test uses a plain tail recursion to sum all the elements in the sequence. The times therefore include more than just the iteration, but the overhead should be small enough not to affect the results:

Here we get the same ranking, with lists coming on top. Coupled with the previous benchmark this demonstrates the strengths of lists. You’re gonna have a hard time finding another structure which is as fast as lists at incremental growth and sequential iteration for sequences of an unknown size. If that is your nail, lists are probably your best hammer.

Tuples come very close, but growing them dynamically will still require building a list. That said, it’s worth noting that walking a tuple-powered sequence may even beat lists in some circumstances. The thing is that you can scan the tuple equally fast in both directions (front to end, or end to front). On the other hand, walking the list in the reverse order will require a body recursion which will add a bit of extra overhead, just enough to be slower than a tail-recursive tuple iteration.

Arrays also show pretty good performance owing to their first-class support for iterations through foldl and foldr. Both perform equally well, so an array can also be efficiently traversed in both directions. On the flip side, both functions are eager, and there’s no support for lazy iteration. In such cases you’ll either have to use positional reads or otherwise resort to throwing a result from inside the fold for early exit.

Maps are significantly slower than the rest of the pack, but not necessarily terrible in the medium range, which we can see if we plot the same data using logarithmic scale with base 10:

Up to 10k elements, a full sequential map traversal will run in less than one millisecond. This is still slower than other data structures, but it might suffice in many cases. It’s also worth noting that maps can be iterated much faster using :maps.iterator and :maps.next. Such iteration is as fast as array iteration, but it’s not ordered, and is therefore not included in this benchmark.

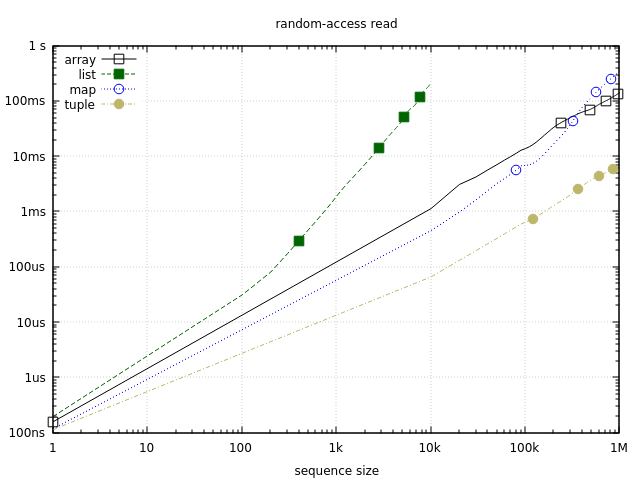

Random-access reads

Let’s turn our attention to random-access reads. This benchmark measures the time it takes to read every element through a positional read. Here are the results:

Note that y-axis value represents the time it takes to read the entire sequence, not just one element, which is for tuples and maps effectively the same as the sequential walk benchmark.

Also note that this graph uses log-10 scale for both axes, which allows us to better see the results for smaller sequences. This scale affects the shape of the curves. Note how the green line starts to ascend faster in the hundreds area. On a linear scale this would look like a standard U-shaped curve skyrocketing near the left edge of the graph.

This benchmark confirms that tuples are the fastest option for positional reads. Given how well they did in the previous two tests, they turn out to be quite a compelling option. This will change in the final test, but it’s worth noting that as long as you don’t need writes, tuples can give you fast random-access reads and sequential scans (both ways), plus they have the smallest memory footprint of the pack (though to build a tuple you’ll need to create a list first).

The 2nd and the 3rd place are occupied by maps and arrays. In the low-to-mid range maps are somewhat faster, while arrays take over in the lower 100k area. In throughput terms, you can expect about few million reads/sec from arrays/maps, and a few dozen million reads/sec from tuples.

The results for lists are a great example of why we should think about performance contextually. For larger sequences lists are terrible at random access. However, for very small collections (10 elements), the difference is less striking and absolute times might often be acceptable. Of course, if you need to do a lot of such reads, other options will still work better, but it’s still possible that lists might suffice. For example, keyword lists in Elixir are lists, and they work just fine in practice.

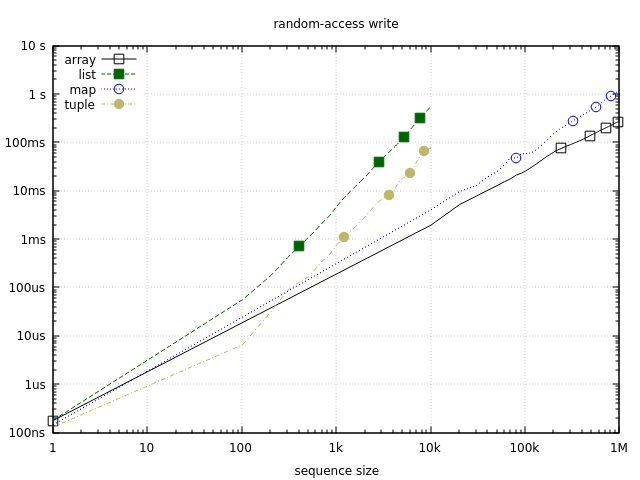

Random-access writes

Finally, let’s see how these structures perform at random-access write operations:

Just like with reads, this graph uses log-10 scale for both axes, with y-axis representing the time it takes to write to every element of the sequence.

On the tiny end (10 elements), tuples are the fastest. This is probably why they are the prevalent option in Erlang for bundling small fixed-size unrelated data (e.g. Erlang records are tuples). I’ve had a few situations where replacing a small map with a tuple (e.g. %{x: x, y: y} with {x, y}) brought significant improvements. That said, the difference usually doesn’t matter, so when I model structured data I still start with maps, using tuples only in exceptional situation where maximum speed is needed.

As soon as the sequence becomes slightly larger, the performance of tuples degrades significantly, while arrays and maps become much better choices, with arrays being consistently better. If frequent random-access writes on medium or larger sequences are what you need, arrays are likely the best option.

Finally it’s worth noting that for very small sequences (10 elements or less), lists will be reasonably fast at positional writes. Their performance might even suffice for a 100-element sequence, taking less than 1 microsecond for a single random-access write. Past that point you’ll probably be better off using something else.

Other operations

I conveniently skipped some other operations such as inserts, deletes, joins, splits. Generally, these will amount to O(n) operations for all of the mentioned structures. If such actions are performed infrequently, or taken on a small collection, the performance of the presented structures might suffice. Otherwise, you’ll need to look for something else.

For example, if you need to frequently insert items in the middle of a sequence, gb_trees could be a good choice. Implementing a priority queue can be as easy as using {priority, System.unique_integer([:monotonic])} for keys.

If you need a FIFO queue consider using :queue, which will give you amortized constant time for prepend, append, and pop operations.

Sometimes you’ll need to resort to hand-crafted data structures which are tailor-made to efficiently solve the particular problem you’re dealing with. For example, suppose we’re receiving chunks of items, where some chunks need to be prepended and others need to be appended. We could use the following approach:

# append seq2 to seq1

[seq1, seq2]

# prepend seq2 to seq1

[seq2, seq1]

If leaf elements can be lists, you can use tuple to combine two sequences ({seq1, seq2}). In either case this will be a constant time operation which requires no reshuffling of the structure internals. The final structure will be a tree that can be traversed with a body recursion. This should be roughly as fast as walking a flat list. If the input elements are strings which must be joined into a single big string, you can reach for iolist (a deeply nested list of binaries or bytes). See this post by Nathan Long for more details.

Summary

As you can see, the list of options is pretty big, and there’s no clear sensible default choice that fits all the cases. I understand that this can be frustrating, so let me try to provide some basic guidelines:

- If you don’t need random-access operations, use lists.

- For frequent random-access operations inside a loop, consider maps or arrays.

- If the sequence size is fixed and very small, tuples could be the best option.

- Tuples might also be a good choice if you’re only doing random-access reads.

Also keep in mind that performance of the structure often won’t matter, for example if you’re dealing with a small sequence and a small amount of operations. Aim for the reading experience first, and optimize the code only if needed. Finally, see if you can replace random-access operations with a chain of forward-only transformations, in which case lists will work well.

It would be nice if we could somehow simplify this decision process, perhaps with a good all-round data structure that wouldn’t necessary be the best fit for everything, but would be good enough at most things. One potential candidate could be Relaxed Radix Balanced Trees (aka RRB-Trees), data structure behind Clojure’s vectors. You can read more about RRB-Trees in this paper and this blog series. With fast times for operations such as append, random-access, join and split, RRB-Trees looks very interesting. Unfortunately, I’m not aware of an existing implementation for BEAM languages.

No data structure can perfectly fit all the scenarios, so I don’t expect RRB-Trees to magically eliminate the need for lists, arrays, or maps. We will still need to use different structures in different scenarios, considering their strengths and weaknesses. That said, I think that RRB-Trees could potentially simplify the initial choice of the sequence type in many cases, reducing the chance of beginner mistakes like the one mentioned at the start of the article.

Comments